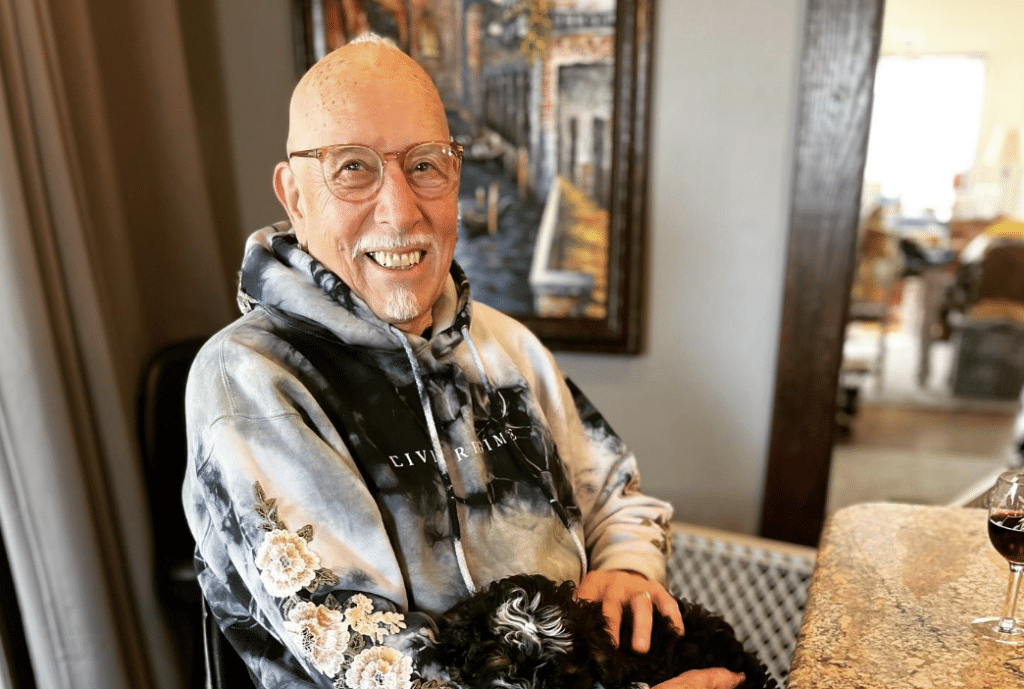

Ernie Baumann, Maywood Arts Champion, Dies at 87

Alongside his wife, Lois, Baumann built Maywood Fine Arts into the premier cultural and arts education nonprofit for Greater West Side youth

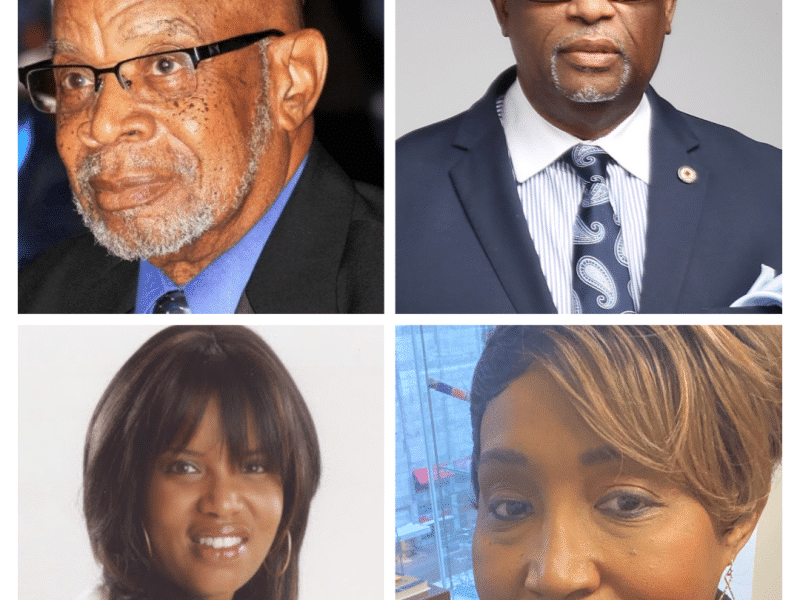

Ernie Baumann, a tumbling instructor, entrepreneur, and community builder whose five-decade mission helped shape the lives of tens of thousands of children across Chicago’s western suburbs and the West Side through Maywood Fine Arts, died on Dec. 28. He was 87. The nonprofit confirmed Mr. Baumann’s death on its Facebook page.

Mr. Baumann and his wife, Lois Baumann, founded Maywood Fine Arts in 1967, transforming what began as modest tumbling and dance classes into one of the region’s most enduring and inclusive youth arts institutions — an organization that today serves thousands of children each week and has produced multiple generations of alumni working across the arts, education, and entertainment industries.

Over the course of 50 years, the Baumanns’ work and marriage survived blizzards, fires, racial and economic upheaval, suburban flight, and the slow erosion of public recreation programs — yet the mission never wavered: to keep arts accessible, affordable, and centered on children.

“The thing that bonded us from the very beginning was our commitment to children, and particularly, at that time, to the children in Maywood,” Mrs. Baumann said in a 2021 interview. “We saw the disparity in what was happening in the country. This was during the Civil Rights Movement.”

Mr. Baumann grew up in Maywood and operated a small neighborhood business, The Newspaper Store, a gathering place for commuters and creatives alike — including a young John Prine, the future Grammy-winning songwriter and fellow Maywood native.

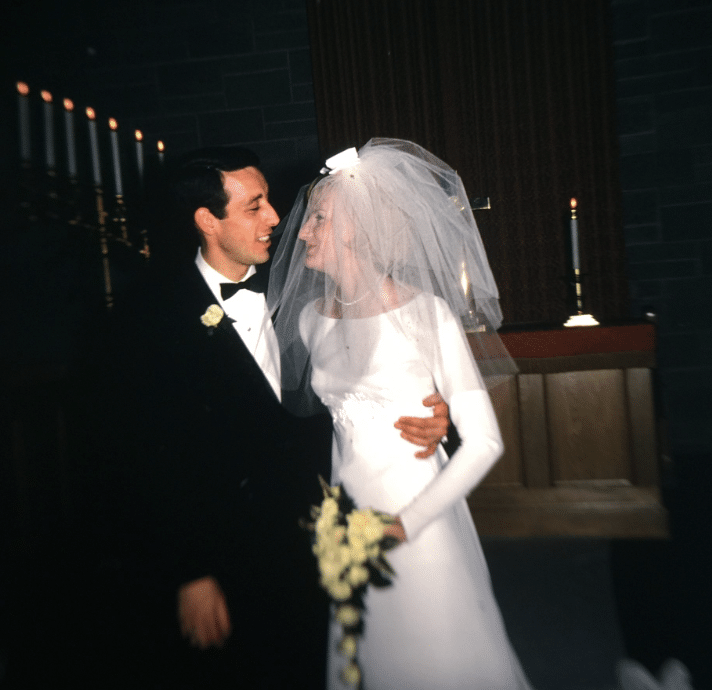

The couple met in 1966, married weeks later — their wedding famously delayed by the historic blizzard of January 1967 — and immediately began building a life defined by service.

They first worked within the Maywood Recreation Department, where Lois taught dance and Ernie taught tumbling, coordinating all-day park programming for neighborhood children.

When village officials attempted to raise fees on their expanding arts programs, the Baumanns walked away.

“They wanted to start raising the prices,” Mr. Baumann recalled. “We said, wait a minute. You’re eliminating people by doing this, which is not the way it should go. So we left and started our own thing and ran it how we thought it should be run.”

That “own thing” became Maywood Fine Arts.

In 2010, a fire destroyed the organization’s beloved home — the former Maywood Opera House, which the Baumanns had transformed into the Stairway of the Stars dance studio.

Former student Craig Hall, who began dancing there at age 4 and later spent 20 years with the New York City Ballet, remembers the phone call vividly.

“She was crying and saying the studio was on fire,” Hall said, recalling the call from the Baumanns’ daughter, Purdie Baumann. “So my dad and I drove over here and saw the flames and couldn’t believe it.”

What followed became one of Maywood’s most cherished stories.

To rebuild, Mr. Baumann mobilized the children themselves.

More than $13,000 was raised — mostly in pennies — through a grassroots campaign called “Raising the Barre.”

“We had these little jars… and hundreds and hundreds of kids would go home, bring the jars back and get another one,” Mr. Baumann said. “We were in there every day.”

By 2016, a $2 million, state-of-the-art dance facility stood in its place.

“When the old studio burned down, it was like a little piece of all of us was broken,” Hall said at the reopening. “But it’s a dream come true.”

Mr. Baumann’s legacy now spans generations.

His granddaughter, India Rose Renteria, a performer since childhood, has already appeared in productions including the Tony Award–winning musical Ragtime. His students continue to dance on Broadway, with major companies, and in classrooms across the country.

Even as Maywood’s demographics shifted dramatically — from 60% white in 1970 to 75% Black by 1980 — and jobs, businesses, and public recreation programs disappeared, Mr. Baumann refused to leave.

“We were right in the middle of ‘White Flight,’” he said. “People would say, ‘You’re leaving, aren’t you?’ We’d say, ‘Huh? We ain’t going anywhere.’”