Despite Protests, the 2024 DNC Wasn’t 1968

‘Clever’ policing, smaller crowds, scarce arrests, and lower crime made this year nothing like ‘68 — as interrelated issues like ceasefire and reparations went overlooked

On Aug. 23, a day after the Democratic National Convention (DNC) ended, Chicago Police Supt. Larry Snelling told reporters that his officers made 74 arrests over the convention’s four days and estimated that no more than 4,000 people turned out to protest on any given night.

The Chicago Police Department (CPD) said shootings and homicides during the DNC’s four days, from Aug. 19 through Aug. 22, dropped by 26% and 31%, respectively, compared to that same timeframe last year.

“Our city was on display,” Snelling said. “And it was on display for the world to see, and I guarantee the world was watching. However, we showed again that this is not 1968.”

By comparison, the Guardian newspaper estimated that during the 1968 DNC in Chicago, police made nearly 700 arrests and over 1,000 people injured—including almost 200 officers—in what government authorities would later call a “police riot.”

In his Substack newsletter on Aug. 25, journalist and bestselling author Jonathan Alter wrote after the convention, he learned from Chicago sources “how the city kept the lid on.”

“It wasn’t just that the numbers of protesters were smaller than expected; the authorities applied [highly effective] crowd control tactics,” Alter reported. “Instead of cars or horses, police used bicycles to block streets when violent outside activists tried to move beyond the designated protest areas. The bike approach mostly worked to quell disturbances […].”

Alter said on the DNC’s last day, he covered a press conference just outside the United Center “in which pro-Palestinian protest leaders angrily complained that a Georgia state legislator — who had spent the night sleeping on a sidewalk near the hall — was not allowed to speak to the convention. Imagine if they were objecting to the arrest of dozens or hundreds of protesters stripped of their constitutional rights and jailed in dank cells. Thanks to clever and humane planning, we didn’t hear a peep about that.”

That Georgia state legislator, Rep. Ruwa Romman, was one of around 30 delegates who earned spots at the DNC after hundreds of thousands of voters wrote “uncommitted” on their ballots to protest President Joe Biden’s support of Israel.

According to Reuters, Palestinian health authorities say, “Israel’s ground and air campaign in Gaza has killed more than 40,000 people, mostly civilians, and driven most of the enclave’s 2.3 million people from their homes.”

In 1968, Democratic Party officials let protests against the Vietnam War spiral out of control, possibly providing fuel to former Vice President Richard Nixon’s “law and order” campaign and helping him beat incumbent vice president and Democratic presidential candidate Hubert Humphrey. Nixon appealed to voters who thought the country was out of control.

This year, no Palestinian was allowed to take the main stage at the DNC, even though Vice President Kamala Harris mentioned Gaza in her acceptance speech on Aug. 22.

“The scale of suffering is heartbreaking,” Harris said. “President Biden and I are working to end this war such that Israel is secure, the hostages are released, the suffering in Gaza ends, and the Palestinian people can realize their right to dignity, security, freedom, and self-determination.”

The Democrats were much more successful at containing protests and controlling the narrative this year — potentially enhancing their chances of taking the presidency — but the containment and tight control may have come at the cost of silencing critics of war crimes and advocates arguing for deep solutions to problems like structural racism and wealth inequity.

The protests were connected

Hours before Harris took the stage on the DNC’s last day, a group of pro-Palestinian activists held a press conference at Union Park near the United Center. Organizers held a banner at the press conference with a message in large, bold letters — “Stand With Palestine! End U.S. Aid to Israel.” Underneath that message, read a series of demands in smaller fonts, including “Stop Police Crimes!” Throughout the park, colorful signs resting on trees read: “Money for jobs, school, healthcare, housing, and environment! Not for war!”

The banners and signs showed how demands at the DNC protests were interconnected, not just isolated to single issues. According to protestors, less money going to Israel to bomb Palestinians meant more potential funding for critical needs for education, healthcare, and housing in underdeveloped places like the Westside.

If Palestine as a single-issue campaign dominated the mainstream media’s narrative of the DNC protests, the march for reparations that occurred on the Westside on Aug. 21 went largely ignored by mainstream media outlets.

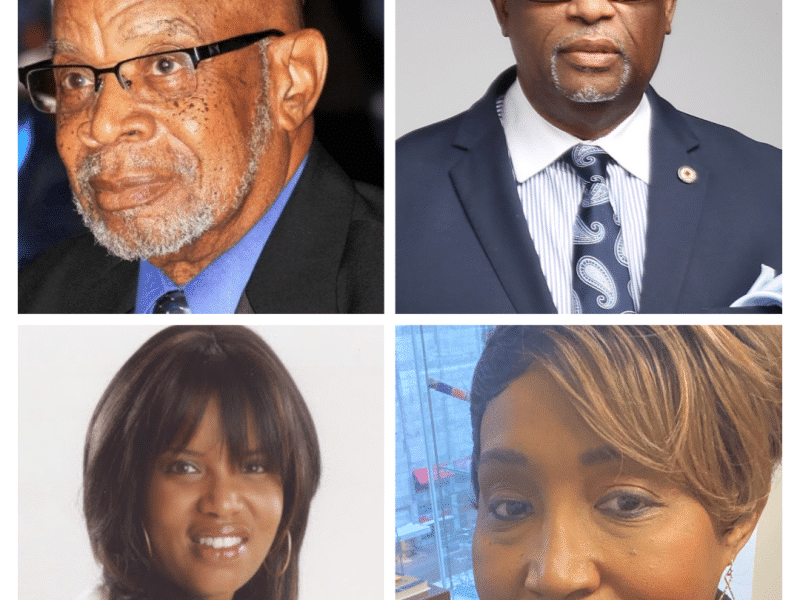

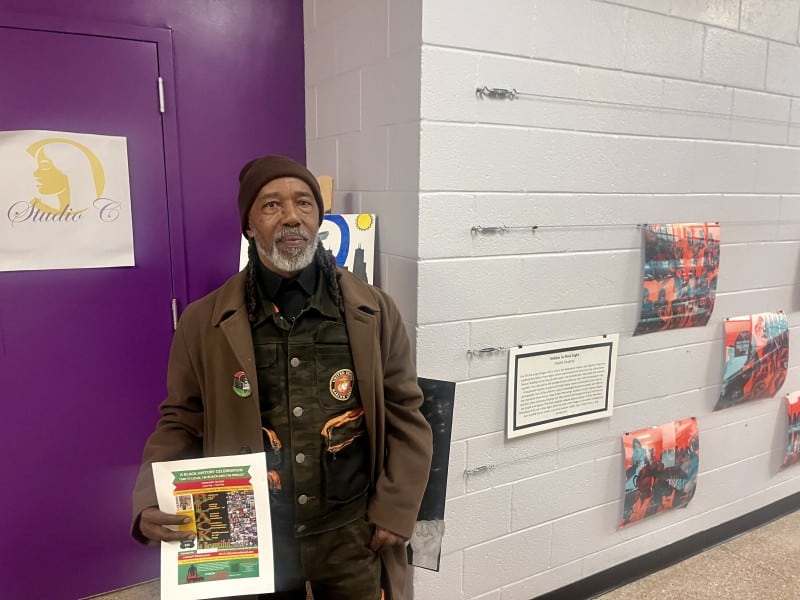

“We are here because we demand reparations!” said Richard Wallace, the founder of Equity and Transformation (E.A.T.), who organized the march that started with a rally at 601 S. California Ave.

Wallace said E.A.T.’s mission is to build social and economic equity for Black informal workers who don’t have access to the formal economy “in a country that demands you have living wages to survive.”

He discussed the five pillars of reparations: restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction, and guarantees of non-repetition.

“People say what are reparations,” Wallace said. “The bag [money] is extremely important. Yes, we want the bag. But other examples of reparations are so much more robust, so I don’t want to cut us short. Reparations has five pillars. The first pillar is to rehabilitate our communities. Another pillar is restitution, or the commitment to restore a survivor of harm to their condition before the harm occurred. That means if you were incarcerated and came home with a record, we’re talking about expunging that record.

“Another very important piece we forget that needs to be highlighted is a guarantee of non-repetition,” Wallace said. “That means they have to commit to not continuing the harm. If you are formerly incarcerated, there’s the 13th Amendment, which preserves slavery in America. If you get locked up, they can pay you $0.17 an hour. We get state pay, because slavery is still legal in the United States of America — as long as you’re convicted of a crime. A guarantee of non-repetition means that that can’t be. That means we gotta amend the 13th Amendment. We gotta end that exception.”

Wallace and other organizers demanded the passage of HR 40, a bill establishing the Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans.

According to Congress.gov, the commission would “compile documentary evidence of slavery in the United States, study the role of the federal and state governments in supporting the institution of slavery, analyze discriminatory laws and policies against freed African slaves and their descendants, and recommend ways the United States may recognize and remedy the effects of slavery and discrimination on African Americans, including through a formal apology and compensation (i.e., reparations).”

Kamm Howard, the co-chair of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’COBRA) and one of the authors of HR 40, placed the demand for reparations in an international context.

“In 2001, in Durbin, South Africa, at the World Conference Against Racism, the international community declared that the trans-Atlantic slave trade was a crime against humanity. They declared that enslavement was a crime against humanity. They declared that Apartheid was a crime against humanity. So, what does that mean? Crimes against humanity have no statute of limitations. If it happened 400 years ago and the entity still exists, they’re criminals today.

“What was apartheid in America called? Jim Crow. We had 246 years of enslavement, which was criminal. We had 90-plus years of apartheid, which was criminal. And we live in a neo-apartheid era right now. Apartheid is separation backed by state violence.”

Howard said “neo-apartheid” exists when apartheid-era policies are still affecting people despite the relative absence of state violence.

“You cannot have mass disparities in education, wealth, health, and housing — in every aspect of life between Blacks and whites — unless there is separate development for these populations,” Howard said. “So, separate development is another name for neo-apartheid.”

Some members of E.A.T. and N’COBRA said they want President Biden to sign an executive order establishing a reparations commission before he leaves office.

After the rally, a few hundred people from different cultures and ethnicities marched and held four other rallies along a route that took them north on California Avenue to Madison Street, east on Madison Street to Western Avenue, south on Western Avenue to Harrison Street, and back toward their starting point on California Avenue.

During the march, they never got closer than roughly a half-mile from the tight security perimeter around the United Center. Despite being roughly two miles from Union Park, where the main Palestine-focused protests occurred, people wearing the colors of the Palestinian flag marched alongside E.A.T.S. and N’COBRA supporters dressed in orange shirts.

“When we talk about reparations, we are not talking about a gift, a charity, or handouts,” said Westside activist and former Chicago mayoral candidate Amara Enyia.

“When we talk about reparations, we are talking about what we demand and deserve … If we say we believe in justice, you cannot have justice without repair. You cannot have justice without accountability. You cannot have justice in this country or any other country without a commitment to reparations.”