Black History Lives in the Details at Austin Pop-Up Museum

The temporary exhibit at the Aspire Center for Workforce Innovation draws on family collections to connect Black history to real lives

The Pullman Porters no longer ride the rails, but on the West Side, their legacy is being carried forward in wool caps, blankets, and stories that once lived quietly inside family homes.

A Pullman porter’s uniform cap — similar to one preserved in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. — now sits on display inside a temporary Black History Museum at the Aspire Center for Workforce Innovation, 5500 W. Madison St. in Austin. Dozens of community members attended the museum’s opening reception on Feb. 1 to kick off Black History Month.

The pop-up museum transforms everyday Black family artifacts into historical testimony, connecting local memory to Black history through labor, art, entrepreneurship, and preservation.

Pullman Porters were thousands of African American men — many of them formerly enslaved — hired by industrialist George M. Pullman in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to serve white passengers traveling across the country in luxury railroad sleeping cars. For generations of Black Americans, the job represented rare economic stability and respectability in a segregated labor market.

The porters’ union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, founded by civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph, became the first predominantly Black labor union to receive a charter from the American Federation of Labor and played a pivotal role in building the Black middle class.

Though the profession no longer exists, its material culture endures.

“These hats sell for $800 and more,” said Rosie Dawson, property manager for Westside Health Authority, one of Aspire Center’s anchor tenants and the organizer of the museum. “A lot of people in Chicago have artifacts like this in their homes because their fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers were Pullman Porters. We have to know what’s in our homes.”

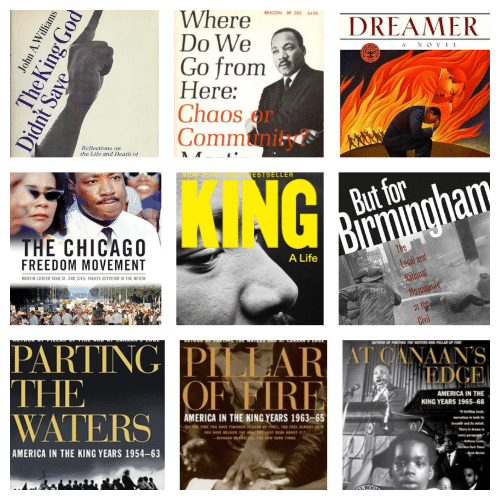

In addition to the Pullman porter’s hat, the museum includes a Pullman blanket and Pullman chair, along with original artwork, vintage magazines from the 1960s and 1970s, and dozens of cookie jars depicting Black figures, including Martin Luther King Jr. Most of the items come from Dawson’s personal collection, built over decades.

“I’m trying to teach our next generation to save what we have,” Dawson said during the opening reception. “Because they are trying to erase our images.”

For Dawson, the work is personal.

“My grandmother had this cookie jar,” she said. “When she passed, they were going to toss it, so I grabbed it, wrapped it up, and put it away. Later, I learned the value of these things and how important it is to keep our own image.”

That idea—preservation as resistance—runs throughout the museum.

Rachel Clark loaned a portrait painted in 1971 by artist Don McIlvaine, created when Clark was 8 years old and her mother, Eunice, was 33. The painting, named after her mother, once hung above the fireplace in the family’s home for decades.

“My mother owned the Pick and Pay store on Madison Street,” Clark said. “She commissioned McIlvaine to do the piece. He took photos of her, and this is what he came up with. We’re not in that house anymore, but we still have the history.”

McIlvaine, a largely underrecognized figure in Chicago’s Black arts history, directed the North Lawndale-based Art & Soul art center from 1969 to 1972, a collaborative project between the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Conservative Vice Lords street gang that also did work in community development.

“People decorate the street because that’s where their life is,” McIlvaine told Time magazine in 1970.

Other pieces in the exhibit explore Black interior life as much as public triumph.

David McCaskill loaned a painting he purchased from his sister, depicting a Black man in chains.

“I love Black art because it depicts our beauty, struggle, and triumph,” McCaskill said. “But in this painting, you see despair. That’s what touches me most. This is an African man in America.”

Another work, “She Wanted Colors,” by artist Mark Pressley, was commissioned by Chawanya Hayes as she prepared to open her first business. Hayes later moved to Dubai, leaving the painting in the care of family members.

“She was opening up her first business, and she wanted something colorful,” Hayes’ cousin, Kesha Forest, explained. “That’s where the title came from. She’s an artist, too.”

Vanessa Stokes, who lent photographs taken by her father, the late West Side photographer Dorrell Creightney, said the museum reframes everyday objects as historical evidence.

“Each artifact is a witness, and it is evidence,” Stokes said. “These are story keepers, reminding us of memories from our upbringing and a history that is distant but very much alive. They tell stories of creativity, resilience, and everyday life.”

U.S. Rep. Danny K. Davis, whose 7th Congressional District includes the Aspire Center, attended the opening reception and said his appreciation for Black art began early.

“I’ve always been intrigued by artistic stuff, intellectual stuff,” Davis said. “I’ve always been a heavy reader, trying to understand these artists — what they did and how they did it — even as a child.”

Unlike traditional museums, the Aspire Center exhibit intentionally blurs the line between the personal and the historical, challenging visitors to rethink what qualifies as an artifact.

“These are not just decorations,” Dawson said. “They are proof. They tell us who we were and who we still are.”

The temporary Black History Museum will remain open throughout February during the Aspire Center’s regular hours, Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.