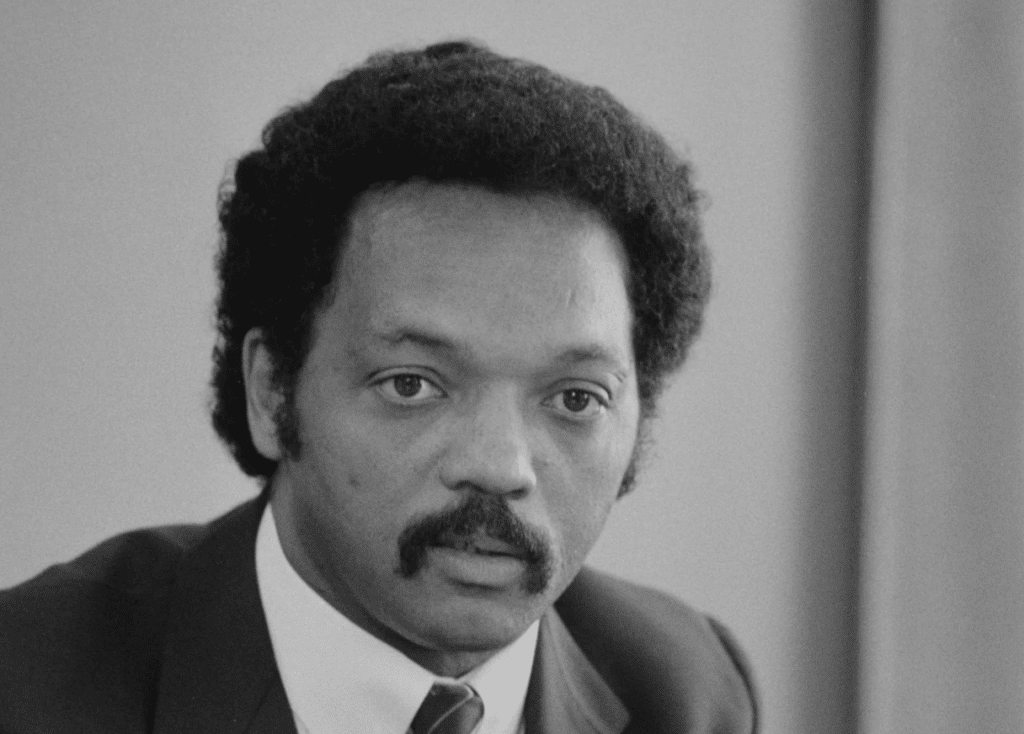

Rev. Jesse Jackson, Civil Rights Strategist and Architect of Modern Democratic Coalitions, Dies at 84

The Baptist minister and activist also influenced clergy, activists, and politicians on the West Side and in the west suburbs

Rev. Jesse Jackson, the Baptist minister, civil rights activist, and two-time presidential candidate whose audacious campaigns reshaped the Democratic Party and helped redefine American political power after the civil rights era, died today, Feb. 17, at age 84, his family said.

A cause of death was not immediately given. In a statement, Jackson’s family said he died peacefully, surrounded by loved ones.

“Our father was a servant leader, not only to our family, but to the oppressed, the voiceless, and the overlooked around the world,” the family said. “We ask you to honor his memory by continuing the fight for the values he lived by.”

For more than half a century, Jackson moved at the intersection of faith, protest, and electoral politics — at once preacher, strategist, diplomat, and provocateur. To admirers, he was the political heir to Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the figure who carried the civil rights movement into the arena of presidential politics and institutional power. To critics, he was an ambitious and polarizing presence whose audacity sometimes strained alliances within the movement itself.

Yet few disputed his influence. Jackson helped build the modern multiracial Democratic coalition, elevated Black political operatives into positions of national authority, and forced the party to expand its conception of who counted as a governing constituency.

From Greenville to the Movement’s Front Lines

Jackson was born in Greenville, South Carolina, and rose to prominence during the civil rights era, working alongside King in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. A charismatic orator steeped in the cadences of the Black church, he quickly became known for his ability to mobilize crowds and frame political struggle in moral language.

After King’s assassination in 1968, Jackson emerged as one of the movement’s most visible — and controversial — young leaders. His rapid ascent unsettled some veteran activists who believed leadership should be conferred collectively, but it also positioned him to carry the movement’s message into new arenas.

In Chicago, particularly across the Greater West Side, Jackson’s presence became intertwined with clergy activism and community organizing that linked the legacy of King to contemporary struggles against inequality. Ministers and organizers would later describe Jackson as a bridge between the moral authority of the civil rights era and the institutional battles that followed, arguing that the unfinished work of King’s generation demanded political engagement, not simply commemoration.

Chicago, the Democratic Party, and a National Stage

Jackson’s political maturation unfolded in Chicago’s rough-and-tumble civic landscape, where he challenged the dominance of Mayor Richard J. Daley’s Democratic machine and helped shape the insurgent coalition that propelled Harold Washington to become the city’s first Black mayor in 1983.

His national breakthrough came with his presidential campaigns in 1984 and 1988. Running as an outsider against the rising tide of Reagan-era conservatism, Jackson built what he called the Rainbow Coalition — a multiracial alliance of Black voters, labor activists, students, Latinos, poor whites, farmers, and peace advocates.

Though he did not win the nomination, his campaigns transformed Democratic politics. He won millions of votes, forced changes to delegate rules, and elevated a generation of political operatives who would later shape the party’s leadership and presidential administrations.

Jackson’s insurgent presidential bids helped reshape the Democratic Party’s coalition and opened pathways for a generation of candidates who followed. Party veterans and historians have long noted that the diverse delegate rules and multiracial electoral strategies that emerged from his campaigns helped normalize the national ambitions of figures as varied as vice-presidential nominee Geraldine Ferraro, Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton and, decades later, President Barack Obama.

His political orbit also produced influential operatives and public figures — from strategists such as Donna Brazile and the late Commerce Secretary Ron Brown to journalists and civic leaders who came of age covering or working within the movement he built — embedding his influence far beyond the elections he himself never won.

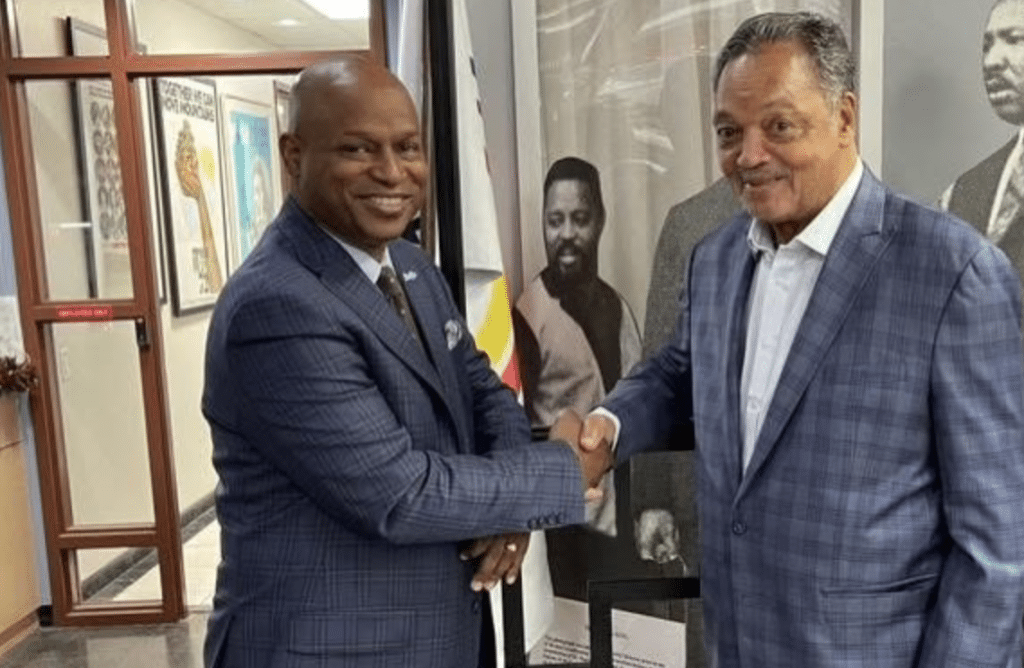

In a statement, Illinois House Speaker Emanuel “Chris” Welch described Jackson as a friend and mentor.

“Rev. Jackson was more than a civil rights icon — he was a builder of hope,” Welch said. “Through the Rainbow PUSH Coalition, he turned pain into purpose and protest into progress. He challenged America to be better, to do better, and to live up to its highest ideals […] He poured into leaders like me, reminding us that public service is about lifting those whose voices too often go unheard. His presidential campaigns inspired a generation to believe that our politics could reflect the full diversity and brilliance of this nation.”

His speeches at Democratic National Conventions — particularly his 1988 address urging Americans to find “common ground” — were widely regarded as among the most powerful political orations of the era, blending biblical imagery with a sweeping vision of pluralistic democracy.

Last month, Rev. Ira Acree, the pastor of Greater St. John Bible Church in Austin, who considered Jackson a mentor, explained the personal effect of Jackson’s convention speeches.

“I first heard Rev. Jesse Jackson, Sr. in 1984, when he visited [the University of Illinois at Chicago’s] old Circle Campus while I was a student there,” Acree wrote on Facebook. “His words changed my life.”

An Unofficial Diplomat and Political Force

Jackson’s activism often extended beyond traditional political boundaries. In 1984, during his presidential campaign, he traveled to Syria and negotiated the release of Lt. Robert O. Goodman Jr., a Black U.S. Navy pilot whose detention had drawn national attention. The successful mission led to an unusual White House ceremony in which President Ronald Reagan publicly welcomed Jackson — a moment that underscored both Jackson’s international reach and his ability to force recognition from political adversaries.

Over the decades, Jackson also pressed major corporations to diversify their leadership ranks through Operation PUSH and later the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, arguing that economic inclusion was inseparable from political justice.

His willingness to engage controversial figures and causes — including his outspoken criticism of U.S. foreign policy and his refusal to fully sever ties with polarizing leaders — made him a lightning rod. Admirers saw a leader willing to absorb personal risk to widen democratic debate; critics accused him of theatricality and divisiveness.

Jackson never held high elected office, but his imprint on American politics was profound. Many of the Democratic Party’s modern coalition strategies, from the centrality of Black Southern voters to the prominence of diverse delegations at conventions, trace their lineage to battles he fought decades earlier.

Figures who emerged from his political orbit — including prominent party strategists and cabinet officials — helped shape the administrations that followed, even as some successors distanced themselves from his more confrontational style.

To supporters, Jackson represented the unfinished promise of a more expansive liberalism, a counter-narrative to the rise of market-driven politics in the late 20th century. To detractors, he symbolized the tensions between movement idealism and electoral pragmatism.

What remained constant was his presence — still preaching, organizing, and speaking well into his later years, his voice a reminder of an era when the boundaries of American democracy felt more open and more contested.

The West Side and the Continuing Struggle

In West Side and west suburban churches and community spaces, where Jackson preached and organized for decades, clergy and residents often spoke of him less as a historical figure than as a living link to a larger struggle.

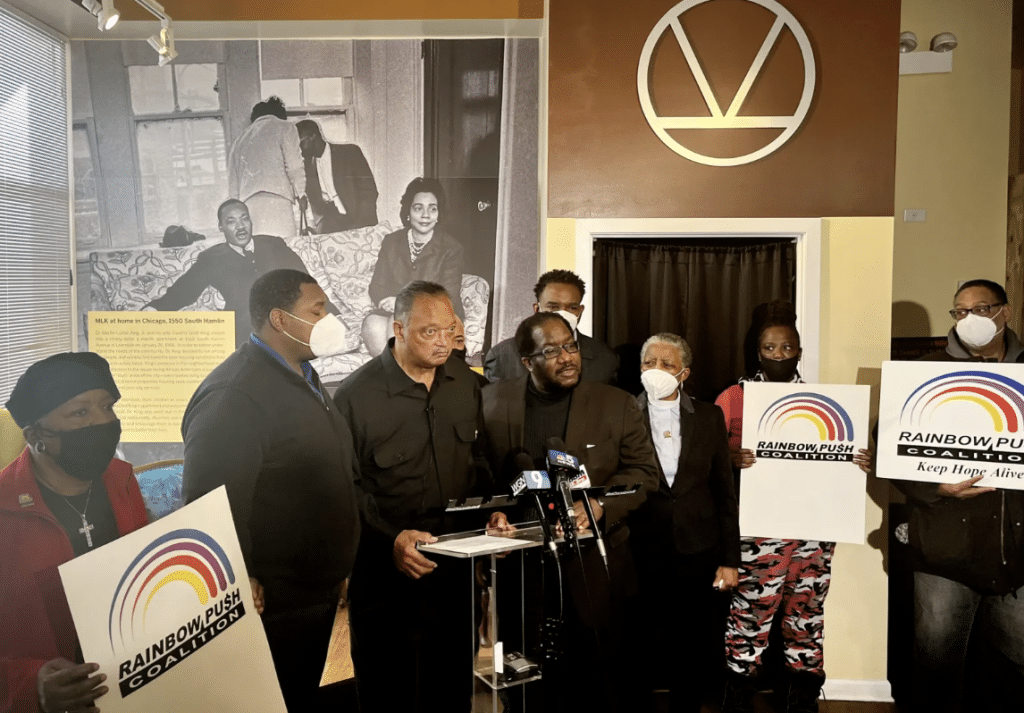

“Clearly the past has not passed,” said Rev. Marshall Hatch, the pastor of New Mt. Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church in Garfield Park and the Illinois president of Jackson’s Rainbow PUSH Coalition, during a Martin Luther King commemoration held in January 2022 at the Dr. King Legacy Apartments at 1550 S. Hamlin Ave. in North Lawndale. Rev. Jackson attended the event where clergy addressed a range of political challenges, including obstacles to the right to vote that Republicans were pushing.

“We’re not [only] here because Dr. King occupied this very space, but we’re here because the struggle is ongoing,” Hatch said. “We’re here back again fighting for the right to vote. That should be fundamental and that was, at one point, a bipartisan agreement — that every citizen has a right to vote. And so, in many ways, we’ve gone backwards and that’s why Rev. Jackson continues to challenge us. We can’t stop marching, we can’t stop standing up. We must continue fighting relentlessly.”

“Dr. King was a West Sider,” said Rev. Ira Acree, who is also a longtime leader within Rainbow PUSH, said at the time. “We say that with pride. Rev. Jackson has challenged us to think about what Dr. King would say today.”

West Side clergy recalled Jackson’s insistence that political power must grow from the margins, and that faith communities should serve not only as sanctuaries but as engines of civic engagement.

For many, his death closes a chapter that began with King’s generation but never fully ended — a reminder that the battles Jackson fought over representation, economic justice, and global solidarity remain unresolved.