Seeing The Westside In A Different Light

Painter and Austin native Jesse Howard talks about his unique technique and how his art is like jazz

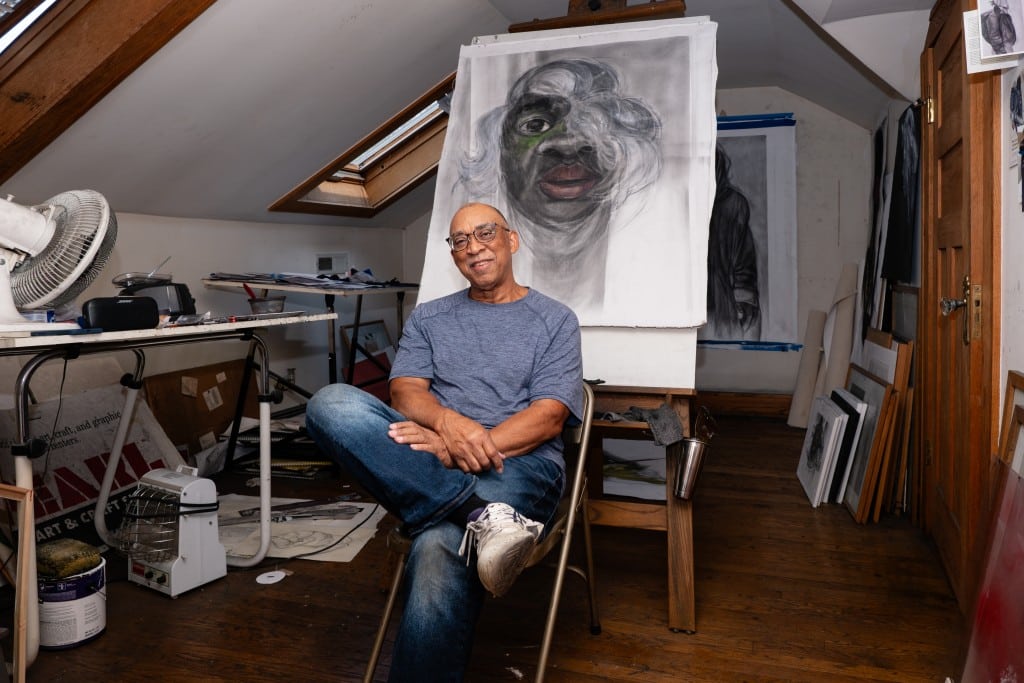

The artist Jesse Howard inside the studio at his Maywood home. Howard, a native of Austin High School, said his art is inspired by his hometown. | Kenn Cook Jr.

“I grew up on 16th Street in K Town, around Pulaski,” prominent artist Jesse Howard said in a 2015 interview.

Howard was among the first group of Blacks to attend Austin High School and played on the school’s football team, which meant that he got chased and softly tormented by whites both late in the day (he had to walk home from practice), as well as in the mornings like his other Black friends who walked to the school.

“We’d all have to gather together on the corner,” he recalled. “They’d get us. We’d have to walk on Pine Avenue and Madison. White folk would get up on the roof and throw eggs at us.”

The experience, though, made him who he is today, he says. It breathes on the canvasses that hold his work—much of it comprising the grotesque faces and forms of men disfigured, silently fuming, angry from what can only be assumed to be any manner of unspoken injustices.

They are, in particular, who Howard calls the “virginally invisible.” Homeless. Disenfranchised. Humiliated.

There is an understated rage in Howard’s work that the Westside native says took him a long time to tap into.

Earlier this month, I interviewed Howard about how his artistry has evolved since our last conversation. The following has been lightly edited for clarity.

Jesse Howard works on a piece in his home studio in Maywood. | Kenn Cook Jr.

A lot of your earlier work is created with charcoal, but you’ve since switched to working with someone else, correct?

Yes. I’m experimenting with Conté crayon [compressed powdered graphite or charcoal mixed with a clay base]. You can get some very deep tones; whether blacks or greys. The thing about it is that it’s unforgivable, but once you use it you won’t want to go back to anything else. I’ve learned how to mix it, though. So, I might mix Conté crayon with charcoal or acrylic paint, giving much more depth to the image.

One of the things that keeps showing up in your work is headward—especially hoods.

I went back to Austin in the 1990s and I started studying gangs. They were wearing hoodies. This was before Trayvon Martin. I just thought it was interesting because the gang soldiers wore the hoods. The leader didn’t have a hood on all the time. He was also involved with them and I learned their hierarchy. Then, it got to the point where I could talk with them because I wasn’t intimidated by them. I grew up in the area and knew I could talk with them. Later on, I started paying attention to disenfranchised folks. Some things about the Westside haven’t changed in 50 years. I wanted to show these folks in a different light.

What are some new focuses of your work?

I’ve done a series on church mothers, the older women who run the church. I haven’t seen many African American artists highlight them positively. I went to my cousin’s church in St. Louis to take pictures and did that series. That started during the pandemic in 2020.

Jesse Howard works on a piece in his home studio in Maywood. | Kenn Cook Jr.

What would you tell people new to fine art but interested in valuing and purchasing it?

They should start with their local galleries. Buy what you like for right now. Develop an appreciation for it, but at some point, it would help to do a little studying. Pick up an art history book or go to a lecture at an art museum. You’ll find that fine art is just as sophisticated as jazz.

Yes. Many people have problems with abstract art, but I found a way to make my work somewhat abstract while pulling you in. For example, if you listen to jazz, you always hear the melody, then the break, and then different chord changes before you start interpreting it. But they always take you back to the melody and the audience never asks what you’re doing. When it comes to visual art, I give you a melody and start breaking down the form. The average person questions that in art, but not in jazz or music in general, because of a lack of knowledge.